If your dog ate something you know is toxic, what do you do? Making him vomit is in many cases the best next step. Always best to call your veterinarian and make sure. There are some things that should not be vomited up, and also some dogs who are poor candidates for vomiting. Also, if the item in question was consumed more than 90 minutes ago, inducing vomit may not be beneficial.

Making a dog vomit is not without risk. It is a violent activity, and some dogs can inadvertently inhale some of the vomitous into their lungs, resulting in a type of pneumonia called “aspiration” pneumonia.

The most common items dogs eat that we veterinarians get asked about are chocolate, sugar free gum (xylitol), raisins, and food items from the trash. Vomiting is a good idea for these! Here’s a list of items and circumstances where you should most likely not induce vomiting:

- Anything with bones in it. Small bones, when vomited, can potentially perforate the esophagus – bad news!

- Gasoline, kerosene, bleach or drain cleaner. These are very caustic and irritating, and can do more damage to the esophagus if they go back up it via vomiting.

- The item was consumed hours ago. It’s left the stomach already, so the vomit ship has sailed.

- If your pet is mentally “off”, or has a history of lung or esophageal disease, do not induce vomiting.

- Brachycephalic breeds (smooshy-faces, like pugs, pekingese, or boston terriers) run higher risk of aspiration, so check with your vet before inducing vomit.

Bottom line – if you are unsure, ask your veterinarian. If your veterinarian is closed, contact your nearest emergency clinic, or the National Animal Poison Control hotline (there is a fee for this).

But, if your healthy happy lab got into the dark chocolate covered raisins, making him vomit is the first step. Hydrogen peroxide works very well as an inducer. A new, unopened bottle of 3% hydrogen peroxide will work the best. Does every dog vomit from it? Nope! Nothing is guaranteed in life, but this is most likely to work. For cats, peroxide does not cause vomiting, and only a veterinarian can induce vomiting in cats. So, this article is about dogs only. Cats just need to go to the veterinarian ASAP. Thankfully, cats rarely eat the crazy things dogs do.

Do not use anything other than 3% hydrogen peroxide. Do not use salt. Do not use syrup of ipecac. Do not use any other idea you may have found online.

If you happen to have syringes at home without needles attached, they may be used. Otherwise, a turkey baster may work as well. Squirt the correct amount of hydrogen peroxide into your dog’s cheek, giving him time to swallow. Yes it will foam. And yes it tastes bad. (Sorry dude, you’re the one who had to get into the trash!)

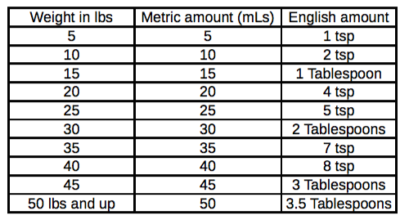

Below is a chart of how much hydrogen peroxide to administer to your dog based on your dog’s approximate weight.

After giving the peroxide, allow 10-15 minutes for vomit. I’d suggest going outside if the weather is at all decent. And watch the dog to see what comes up! Also, some dogs will eat vomit (hey, they eat poop, so why not?) so monitor your dog to make sure the item you’re working so hard to remove from his system does not get re-consumed. It’s always good to examine what comes out to get an idea of how much might still be in the dog.

If 15 minutes go by and your dog has not vomited, repeat the dose of peroxide. You may only repeat the dose one time. Still no vomit? Time to go to the vet. Besides, dogs love to vomit in the car. 🙂 (Bring some towels just in case).

In many cases, vomiting alone is sufficient, particularly when it’s right after the ingestion. With other toxins, vomit is the first step, but a medication called activated charcoal needs to be administered by a veterinarian. This will absorb the toxins that remain in the dog and stop them from causing harm to organs like the liver and the kidney. Depending on the toxin and the amount consumed (and vomited) some dogs may require blood tests or even hospitalization.

And finally, if you do end up going to the veterinarian, bring the bag, wrapper, or container of whatever your dog ate with you. Knowing precisely what your dog ate will help the veterinarian know which treatments are needed, and which are not.